Laylow: Tank top, Givenchy. Pants, Dior Homme. Necklaces, Givenchy.

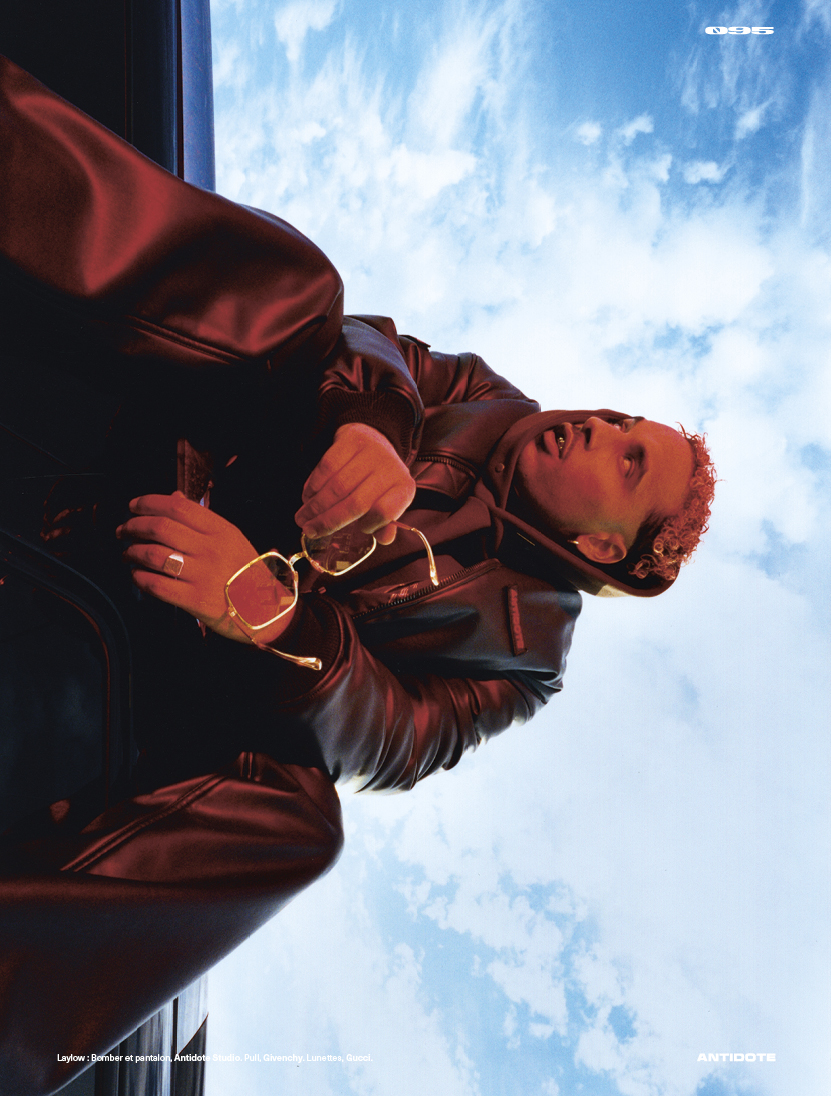

Laylow: Tank top, Givenchy. Pants, Dior Homme. Necklaces, Givenchy. Laylow: Bomber and pants, Antidote Studio. Sweater, Givenchy. Glasses, Gucci.

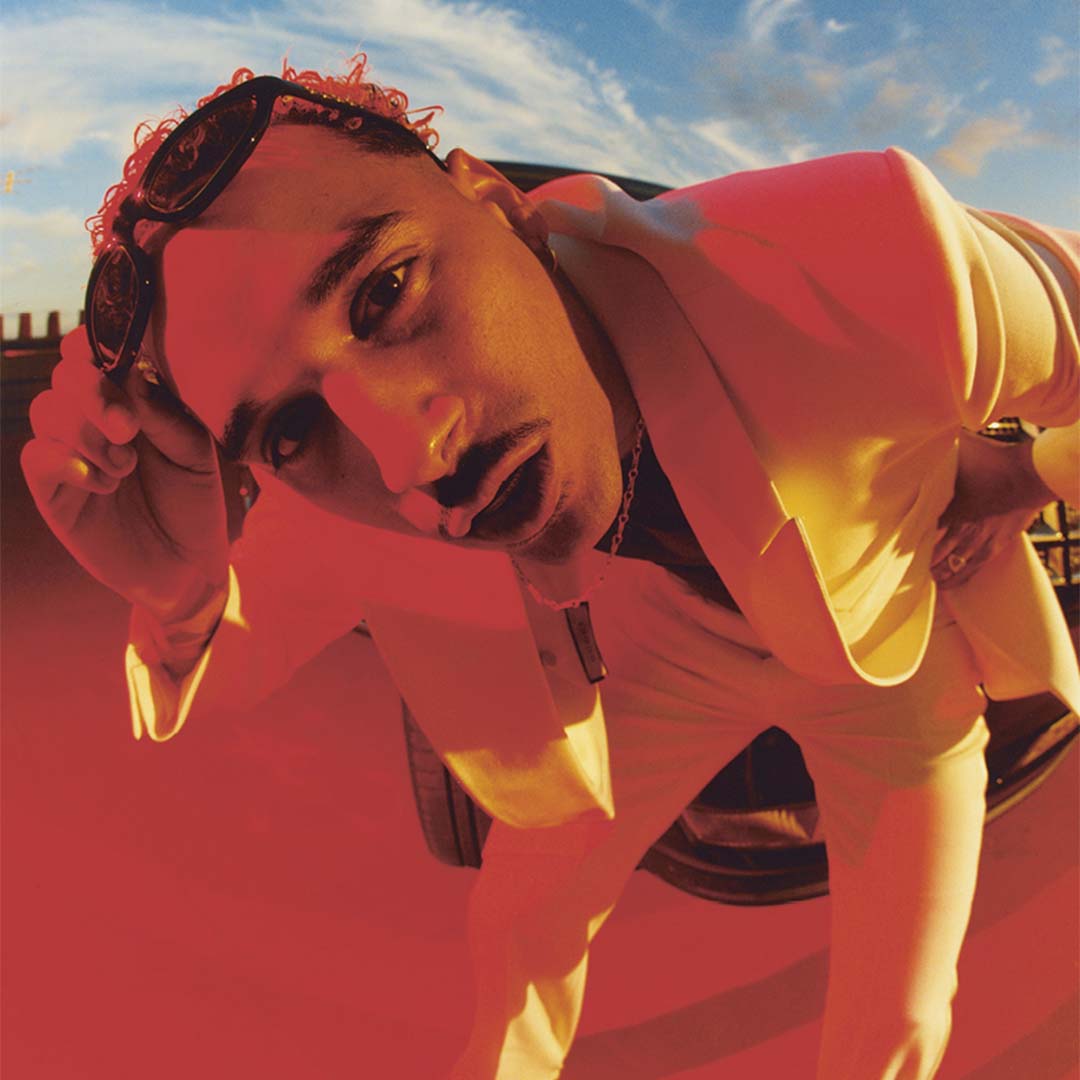

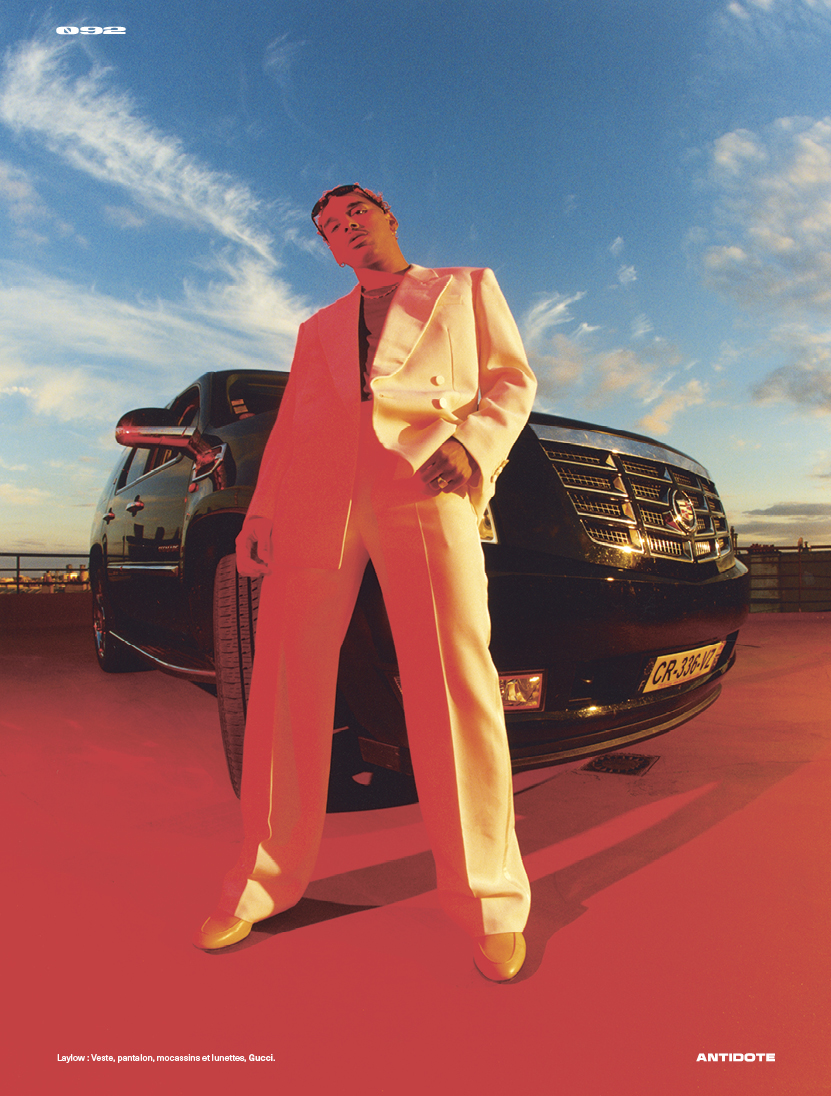

Laylow: Bomber and pants, Antidote Studio. Sweater, Givenchy. Glasses, Gucci. Laylow: Jacket, pants, loafers and glasses, Gucci.

Laylow: Jacket, pants, loafers and glasses, Gucci. Laylow: Bomber and pants, Antidote Studio. Sweater, Givenchy. Glasses, Gucci.

Laylow: Bomber and pants, Antidote Studio. Sweater, Givenchy. Glasses, Gucci. Laylow: Turtleneck, Dior Homme. Pants, Antidote Studio. Glasses, Tom Ford.

Laylow: Turtleneck, Dior Homme. Pants, Antidote Studio. Glasses, Tom Ford.