While anthropological, sociological, and philosophical interest in fashion and its output has been well documented and conveyed for many years, psychology, psychoanalysis, and even psychiatry have remained strangely in the shadows. However, after careful consideration, one can’t help but notice that fashion and the objects it produces in order to enable people to compose their own “ornamentation” – as it is referred to in anthropology – have long been of interest to researchers in these disciplines. From the publication of works detailing the connections between fashion and the unconscious, to experiments analyzing the impact of clothing on our cognitive capacities, the incorporation of specific wardrobes in certain therapeutic treatments, and even the appropriation of the lexical field of psychology in statements made by luxury brands, let’s take a look at fashion and the cognitive sciences’ mutual attraction.

What does the way we dress reveal about us? Can clothes have an impact on our mood, our behavior? Can fashion and its different products (clothes, accessories, make-up…) contribute to our psychological well-being? Both a social mask and a non-verbal language, clothing – as the primary element of the adornment we wear – is a precise and valued indicator of the way we look at ourselves, and of the self-image we want to present to others and to the world. From Roland Barthes to Jean Baudrillard and Georg Simmel, many intellectuals from different fields, primarily the humanities, have devoted part of their work to fashion, ornamentation, and/or clothing. But other cognitive sciences such as psychology have shown little interest in the matter – an omission that is, without a doubt, due to a perception that lingers in the collective imagination of the frivolous, petty, and futile nature of fashion and of everything that even remotely has to do with appearances.

Toward a Psychology of Clothing

Since the 1920s and the beginnings of psychoanalysis, major figures such as Sigmund Freud and John Carl Flügel have attempted to identify and explain the psychosociological implications of fashion and clothing. In 1929, the Revue Française de Psychanalyse (French journal of psychoanalysis) reprinted a lecture delivered by Flügel titled “De la valeur affective du vêtement” (On the affective value of clothing), while Freud turned his attention to fetishism. The same year, the American psychologist Elizabeth B. Hurlock published The Psychology of Dress: An Analysis of Fashion and Its Motive, a study that seems to have remained relatively unknown, while the following year, The Psychology of Clothes by Flügel was released, a milestone essay that is still considered to be the first Freudian-inspired analysis of fashion and clothing. In this text, the psychologist and psychoanalyst developed the idea that clothing serves as an intermediary between the child’s desire to exhibit their naked body and the social prohibition that represses the body by requiring it to be clothed for the sake of modesty. Relying on Freud’s second topography, according to which the mind is divided into three parts (the id, the ego, and the super-ego), John Carl Flügel argued that clothing was used to reconcile the demands these three opposed forces make on the human body and the psyche. For, if the human being is born in a state of narcissistic self-love, the result is a “tendency to admire one’s own body and to display it to others, so that others can share in the admiration. It finds a natural expression in the showing off of the naked body and in the demonstration of its powers, and can be observed in many children.” Seeking to understand what motivates the act of dressing up, Flügel continued: “Clothes are, however, exquisitely ambivalent, in as much as they both cover the body and thus subserve the inhibiting tendencies that we call ‘modesty,’ and at the same time afford a new and highlight efficient means of gratifying exhibitionism on a new level.” Thus, clothing serves a primary narcissistic need and allows one to escape the gaze of the other, while also seeking out the other’s attention. It offers a compromise between a desire for exhibitionism and the need to repress it. This paradox, Flügel notes, is “the most fundamental fact of all the psychology of clothing.” In 1953, psychoanalyst Edmund Bergler published another landmark text, Fashion and the Unconscious, based on Flügel’s theories.

Photo: Gucci Fall-Winter 2022/2023.

Photo: Gucci Fall-Winter 2022/2023.

Despite the dearth of research on the connection between fashion and psychoanalysis, the few works on the subject have paved the way for more contributions to the field, like Trendy, sexy et inconscient. Regards d’une psychanalyste sur la mode (Trendy, sexy, and unconscious. A psychoanalyst’s take on fashion) (PUF, 2009) by psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Pascale Navarri, and La Robe de Psyché: Essai de lien entre psychanalyse et vêtement (Psyche’s dress: Essay connecting psychoanalysis and clothing) (L’Harmattan, 2015) by psychotherapist Catherine Bronnimann, a former designer and professor of design and psychosociology of fashion and appearances at the Haute école d’art et de design of Geneva. Catherine Bronnimann, who draws on Freud’s second topography as well, also positions her thinking within the lineage of analytical psychology developed by psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung – the originator of the psychological concept of the “persona,” which designates the interface between the individual and society, a sort of social mask that defines us from the outside; its ornamentation in the form of clothing constitutes ones of the persona’s most privileged avatars, if not the one we master best. “The persona is a complicated system of relations between the individual consciousness and society. It is a relatively suitable kind of mask which, on the one hand, is calculated to make a definite impression upon others, while, on the other, it cloaks the true nature of the individual,” writes Jung in his 1928 The Relations between the Ego and the Unconscious. “… Most of the time, clothing stands for something other than itself: it stages representations of the world,” adds Catherine Bronnimann, before going on to quote the British anthropologist Julian Pitt-Rivers: “Clothing is always a way of presentation of oneself, and therefore a commentary on other people one assimilates to or differentiates oneself from.” Saveria Mendella, a PhD student in fashion anthropology and linguistics, explains: “Clothes are the first object we decode when facing another body. We make an almost instantaneous value judgment. But each individual who creates their own adornment does this knowingly.

La piel que habito

“A concept of the self that we wear,” as the writer Henri Michaux notes, garments and their finery can be considered mirrors of the psyche. And whether accurate or distorting (voluntarily or unconsciously so), they have become important signs for certain psychotherapists. The psychiatrists Catherine Joubert and Sarah Stern have endeavored to dissect these signs in their book Déshabillez-moi. Psychanalyse des comportements vestimentaires (Undress me: the psychoanalysis of clothing behavior) (Hachette, 2005). Across several vignettes, they analyze different clothing behaviors and what they say about who we are, who we would like to be or, conversely, who we do not want to be.

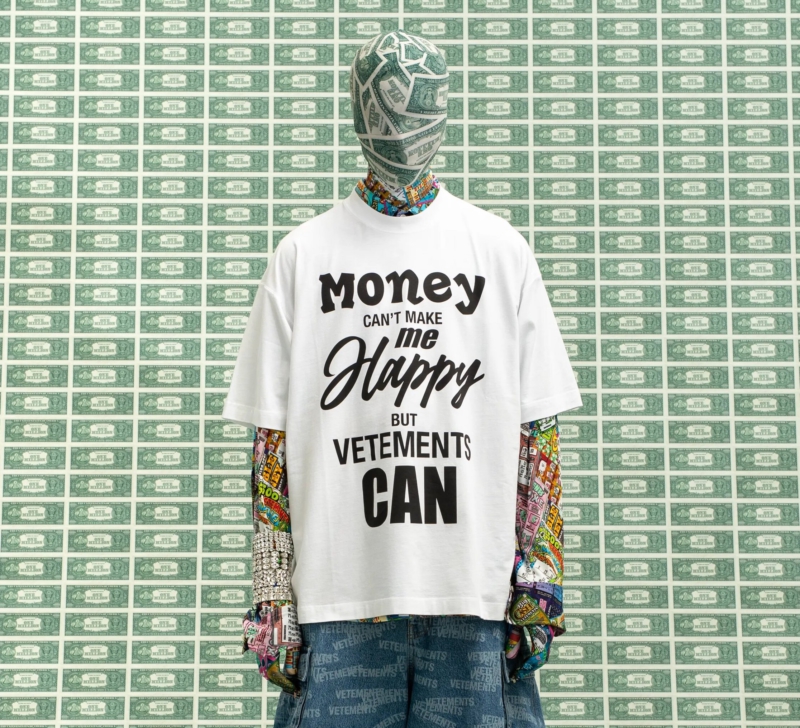

Photo: Vetements Fall-Winter 2022/2023.

Photo: Vetements Fall-Winter 2022/2023.

“I pay a lot of attention to the way my patients dress,” says Michèle Battista, a child psychiatrist who practices at the CHU-Lenval in Nice, where she treats survivors of rape. “When a teenager comes to the clinic in the middle of the summer wearing long sleeves, for example, you wonder if they’ve cut themselves, or why it is that they aren’t affected by the heat, or why it’s so important for them to be so hot.” For her part, Catherine Bronnimann writes, “I am always captivated by wardrobe changes that occur during the therapeutic process.” But rather than simply being revealing, does this second skin – clothing – have the capacity to align with the first? Michèle Battista is convinced it does, especially in the case of illnesses related to self-esteem, such as anorexia.

Maryline Bellieud-Vigouroux: “Clothing can mend the soul. Medicine can’t fix everything. I remember a young girl who used to cut herself. I told her: ‘Listen, if you have the urge to cut yourself again, just tear up the garment instead!’ She stopped cutting herself from that point on because she liked the clothes.”

At the end of the 1990s, she was Marcel Rufo’s right-hand woman during the creation of L’Espace Arthur at the Timone hospital in Marseille, one of the first psychiatric care units in France entirely devoted to adolescents. There, she participated in setting up a “clothing library,” a new space where ill-at-ease teenagers could go, accompanied by the nursing staff, to try on and borrow designer clothes, supplied each season through a collaboration with Maryline Bellieud-Vigouroux, founder of the Maison Mode Méditerranée and initiator of the clothing library. “The idea was to work on the psychosomatic identity of teenagers. There were bins filled with clothes, in a room with mirrors. With the clothes, we were able to influence the teenagers’ self-image. The project won the support of the hospitalized adolescents, who forgot about their illnesses. The body, an object they all but forgotten became the main subject again,” she says. “Many of them did not even try on the garment at first; they just touched the fabric. That was the first contact. And then, little by little, they dared to try the clothes on in front of a mirror, and borrow them,” continues Maryline Bellieud-Vigouroux. “Clothing can mend the soul. Medicine can’t fix everything. I remember a young girl who used to cut herself. I told her: ‘Listen, if you have the urge to cut yourself again, just tear up the garment instead!’ She stopped cutting herself from that point on because she liked the clothes. They had an impact on her psyche and on her own skin, which she hated, but which the garments helped her to respect.” Dr. Battista agrees: “The more beautiful a garment is, in terms of what it represents to us, the more likely we are to feel good in it. It boosts self-esteem. This is very important. Today, I work in trauma, and when you’ve been traumatized, you only see yourself through that trauma. Buying a piece of clothing for a reason other than its use-value is a way of projecting oneself anew. Clothes can help you restart your life.”

Saveria Mendella: “Overconsumption and ready-to-wear have led us to think that we can change our look as easily as we can change our mood.”

Although it did not win the support of all the medical staff at the time, this initiative, which consisted in turning clothing and fashion into therapeutic tools akin to medication, has a good track record. It was later adopted in Paris, at the Maison de Solenn, a unit for adolescents at Cochin Hospital, now run by psychiatrist Marie Rose Moro. “It unleashed Pandora’s box! In the beginning, people asked me if the vêtothèque [clothing library] implied that we were using animals in treatment, as ‘vet,’ also in the word ‘veterinarian,’ might suggest. I don’t get those kinds of questions anymore,” says Michèle Battista, who is currently looking for people who might be interested in helping her set up a new clothing library in Nice. Created in an empirical manner, clothing libraries were not the subject of scientific studies at the time. “We started from an emprirical premise. The idea was to use clothing as a second skin, as an interface between the bodily self, the thinking self, and the self that relates to others. The problem is that fashion always has a financial connotation. But fashion therapy can also be about the pleasure of touching a fabric, the impact of its colors on the eye. Sight, the sensorial, are stimulated.”

Writing Oneself

Fashion’s curative dimension is not reserved only for those who consume it. In September 2021, Olivier Rousteing, who suffered severe burns after a chimney explosion in his home, described the therapeutic effect that designing clothing for the Spring/Summer 2022 Balmain collection had on him, bringing his physical and psychological process of healing to a culminating point. When he revealed dresses made of bandages, directly inspired by those he had to wrap himself in for many long weeks, the designer took the opportunity to share his experience, which he had kept quiet for a year, on Instagram: “I don’t really know why I was so ashamed, […] maybe because of the obsession with perfection in the fashion world and because of my own complexes. […] While I was recovering, I worked day in and day out to forget and create all my collections. I tried to continue to make the world dream, while I hid my scars under my mask, turtlenecks, long sleeves, and even many rings on my fingers. […] My last show [Spring/Summer 2022, editor’s note] was about celebrating the healing that overcomes pain.”

As Dr. Battista has argued, clothing is a “physical and psychic extension of the self” and it allows for the construction of one’s self-narrative. Whether people put effort into their style or pretend not to pay attention to it, each person tells their own story through their relationship to clothing – it’s a kind of self-storytelling. It is not uncommon to hear people who are particularly eager to match their clothes to their mood, say that they have nothing to wear while they are getting dressed. “Overconsumption and ready-to-wear have led us to think that we can change our look as easily as we can change our mood,” says Saveria Mendella. “That absurd phrase ‘I have nothing to wear’ is uttered only because we have tons of clothes at our disposal. When clothing was tailored to conform to widespread conventions, it was a given. But nowadays, clothing is used to individuate oneself. That’s why we talk about ‘adornment’ in anthropology. We are looking for maximum individuality.” Some in the fashion industry have addressed this by implementing tools to make targeted recommendations to consumers, according to their personality and psychology. Launched in April 2021 by Anabel Maldonado as a counterpart to her website, The Psychology of Fashion, which aims to “examin[e] why we wear what we wear” through articles like “What Your Personality Traits Reveal About Your Style” or “What is Dopamine Dressing?,” the Psykhe platform uses artificial intelligence to recommend a selection of pieces that supposedly correspond to each customer’s personality, which is assessed with a test based on the “Big 5” model developed by the American psychologist Lewis Goldberg to define different psychological profiles. On the fast fashion side, in 2017, Uniqlo tested a machine in its Sydney store called Umood, which uses neuroscience to analyze brain waves in the frontal lobe thanks to a helmet equipped with sensors. This allows the consumer, who is exposed to a series of images, to find, among a plethora of T-shirt options, the one that supposedly matches their mood.

Reality and Appearances

Today more than ever, fashion seems to be about mood and psychology. At Prada, for instance, the aptly named Spring/Summer 2022 campaign, “In the Mood for Prada,” features actors Tom Holland and Hunter Schafer dressing and undressing. Exploring “the layers that distinguish and dress one’s inner and outer self,” the campaign is inspired by the emotional connection between the self and clothing. “The way we dress, the mood we wear,” reads the caption to one of the photos of Tom Holland, who, according to the fashion house, “here becomes an embodiment of today’s Prada man – a rich internal life informing his outer projection of self.”

In this way, fashion has made psychology, psychiatry, and psychoanalysis the subject of some of its discourses. “Brands have begun to undertake a self-reflexive process, with artistic directors like Alessandro Michele,” says Saveria Mendella. In the press statement for his latest collection, “Exquisite Gucci,” presented at Milan Fashion Week Fall-Winter 2022/2023 in a hall of distorting mirrors, the designer writes: “Clothes are capable of reflecting our image in an expanded and transfigured dimension… wearing them means to cross a transformative threshold where we become something else.”